The Templar Revelation by Lynn Picknett & Clive Prince

Disclaimer

I am a Pagan and have no dog in the fight of intra-Christian theological disputes. I am merely presenting some interesting passages from the book in question. Some food for thought, if you will! Moreover, presenting the thoughts of the book does not necessarily mean that I endorse them.

Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code

The Templar Revelation was an influence for Dan Brown in writing his most famous work The Da Vinci Code. The book caused quite the stir when it was released. A main part of plot in that book is that Mary Magdalene (carrying the child of Jesus) fled to Europe and that this sacred bloodline has existed since then – this is also the hypothesis laid forth by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln in The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (which I have yet to read). I read The Da Vinci Code when I was 17 and greatly enjoyed it. The religious nuances were beyond me at the time (having grown up in Atheist Sweden, I did not have any references in this regard), but the sense of mystery appealed to me. I have read a few more books by Dan Brown – Inferno, with the philosophical theme of overpopulation, was quite intriguing. Origin was not particularly compelling – I got very Liberal vibes from reading it.

Was Jesus a Magician of the Egyptian Religion?

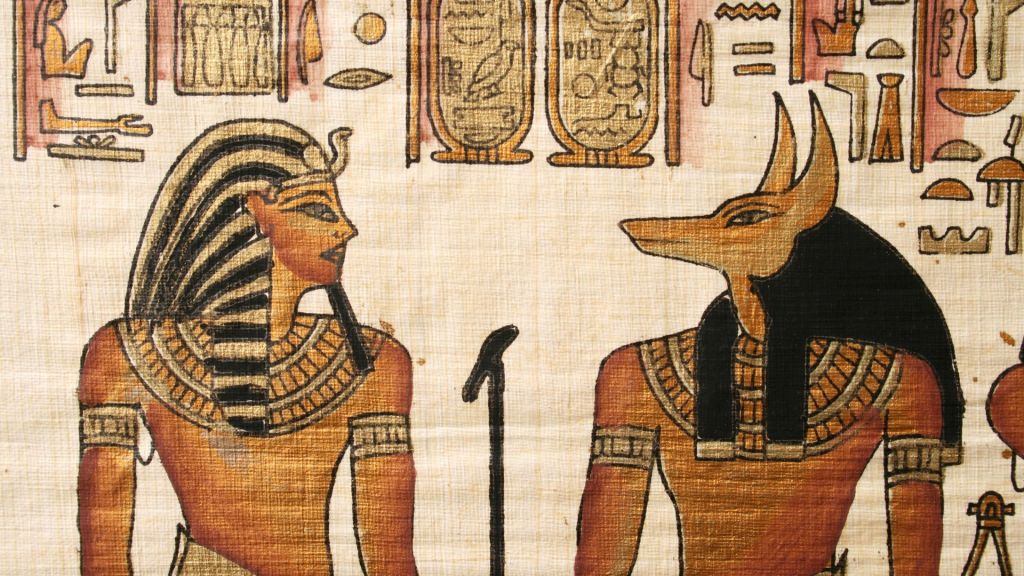

Perhaps the most contentious claim of The Templar Revelation is that Jesus was not of the contemporary Jewish religion (although ethnically Jewish), but rather a worshipper of Osiris and Isis – i.e. of the ancient Egyptian religion. The authors propose the theory that Jesus and Mary Magdalene were initiates of this tradition – and, moreover, that they engaged in sacred sex rituals. They make a compelling case for this, although I am certain that many a knowledgeable Christian would find arguments galore in counter to this.

Pagan Influences on Christianity

A central theme of the book is Pagan influences on Christianity:

‘The shared birthdate of 25th of December is not the only similarity between the Jesus story and that of the pagan gods. Osiris, for example – consort of Isis – died at the hands of the wicked on a Friday and was magically ‘resurrected’ after being in the Underworld for three days. And Dionysus’ mysteries were celebrated by ingesting the god through a magical meal of bread and wine, symbolizing his body and blood.’

Lynn Picknett & Clive Prince – The Templar Revelation. Page 302.

The authors note the following regarding the teachings of Jesus taking hold in the Roman Empire:

‘This explains, they say, ideas such as Jesus’ deification: he had to become known as the Son of God – literally God incarnate – to appeal to the romanized world, which was used to the idea that its rulers and heroes became gods.’

Lynn Picknett & Clive Prince – The Templar Revelation. Page 312.

This reminds us about a passage in The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity by James C. Russel (review):

‘Both Greek and Roman influences contributed toward some degree of an Indo-Europeanization of Christianity, not by actively seeking to do so, but as the passive result of the rapid expansion of Christianity to include people in whom the traditional world-accepting Indo-European world-view remained alive and meaningful.

This prior Indo-Europeanization of Christianity may have eased its acceptance within a Germanic society which retained the traditional Indo-European world-view long after it was supplanted in the classical world.’

James C. Russel – The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity. Page 133.

A good example of deification is that of the Roman Emperors (deified upon death).

Isis and the Virgin Birth

In discussing the similarities between the Egyptian religion and Christianity, the authors share the following insightful passage:

‘And, traditionally, Isis was shown standing on a crescent moon, or with stars in her hair or around her head: so is Mary the Virgin. But the most strikingly similar image is that of the mother and child. Christians may believe that statues of Mary and the baby Jesus represent an exclusively Christian iconography, but in fact the whole concept of the Madonna and child was already firmly present in the cult of Isis. Isis, too, was worshipped as a holy virgin. But although she was also the mother of Horus, this presented no problem to the minds of her millions of followers. For whereas modern Christians are expected to accept the Virgin birth as an article of faith and an actual historical event, the followers of Isis (Isians) and other pagans faced no such intellectual dilemma.’

Lynn Picknett & Clive Prince – The Templar Revelation. Page 99.

On the same page the authors note that the Gods were understood as living archetypes – not historical characters. In the same chapter the authors also note that the worship of most major Goddesses emphasised their femininity by dividing it into three main aspects – each representing a woman’s lifecycle: the Virgin, the Mother, the Crone. Thus, Isis was worshipped as a Virgin and a Mother – but not as a Virgin Mother.

On a personal note, I do not believe in the Virgin Birth of Jesus – I am sorry Peter and Wiktor 😉

Black Madonnas

A hypothesis presented in the book is that the Black Madonnas found in Europe (primarily southern France) are a sign of the survival of Goddess worship. The Goddess (in some cases Isis) was venerated as Mary (Mother of Christ) once Christianity became the dominant religion. Although the authors do not discuss this, it must be noted that the blackness of the Madonnas does not refer to skin colour or ethnicity – rather, the esoterico-magical meaning of black is, in this case, the earth (Mother Earth, fertile earth, fertility). Earth is, as will be known to enthusiasts of Elemental Magic, a feminine element (together with Water – Fire and Air are masculine elements).

Pictured below: Statue of Our Lady of Montserrat (Black Madonna).

Templars and Cathars

As I note in Demigod Mentality, Julius Evola juxtaposed the Templars – bearers of a martial Hyperborean esoteric tradition – against the Cathars, in whom he saw a return to a true Christianity (in his view passive and feminine). The authors of The Templar Revelation approach the two (Templars and Cathars) in a different fashion. Interestingly, they note that the Templars did not take part in the Albigensian Crusade (the crusade against the Cathars) and that they even gave refuge to Cathars fleeing the onslaught of crusaders. Their hypothesis is that the Templars were guardians of a heretical tradition of Christianity – which led to their destruction in 1307. As enjoyers of my work will be familiar with, my own analysis is more rooted in realpolitik – the Templars were mighty and rich, and the French king had no interest in having a powerful entity in his kingdom not directly beholden to himself. In regard to the Albigensian Crusade, a straightforward realpolitikal analysis is that the French king wanted to bring the (culturally quite different) south of France under firmer control.

Perhaps the Templars were, in fact, ‘guilty’ of the charges of heresy levelled against them. Perhaps there was indeed a greater spiritual dimension to their destruction. I must meditate upon the matter further.

In the chapter titled The Templar Legacy, the authors share the following beautiful and inspiring story:

‘In Germany there was a wonderfully hilarious scene. Hugo of Gumbach, Templar Master of Germany, made a dramatic entrance into the council convened by the Archbishop of Metz. Arrayed in full armour and accompanied by twenty hand-picked and battle-hardened knights, he proclaimed that the Pope was evil and should be deposed, that the Order was innocent – and, by the way, his men were willing to undergo trial by combat against the assembled company… After a stunned silence the whole business was abruptly dropped and the knights lived to assert their innocence another day.’

Lynn Picknett & Clive Prince – The Templar Revelation. Page 163.

Conclusion

In my humble opinion, you can read this book and gain new perspectives and insights without necessarily accepting all claims presented therein. I found it worthwhile to read and can recommend it to those who are interested in these matters. The book is 532 pages long and is rigorously footnoted (i.e. plenty of references). A lot more can be said about the book; perhaps we will return to the topic later on!

You must be logged in to post a comment.