Rome and Persia – The Seven Hundred Year Rivalry by Adrian Goldsworthy

Posted on October 16, 2023

I have had the pleasure of reading Rome and Persia – The Seven Hundred Year Rivalry by British historian Adrian Goldsworthy. As the title suggests, the author details the relationship – the many wars but also the mutual respect and sometimes cooperation – between these two great empires.

A Reservation and a Correction

Although the book is otherwise excellent, I must mention two passages that unfortunately detract from the experience of reading the book. In the introduction the author states the following: ‘In an ugly form, the claim that Germans were different from other Europeans because they had thrown off the Roman yoke…‘. This sentence struck me as rather absurd – in my humble opinion it is fully natural to be proud of the fact that most of Germania was not conquered by the almighty legions. Later on the same page, the author uses the word ‘N*zi,’ which is a word that should never be used by a serious scholar.

Later on in the introduction, the author states that ‘Greeks and Romans were equally disparaging about all other outsiders…’ – this is simply not true. The Roman historian Tacitus famously extolled the virtues of the Germanic tribes – juxtaposing said virtues against the decadence of the Romans. This is in rather sharp contrast to how they viewed most other peoples (especially those to the east) that they encountered. Funnily enough, the author mentions the following in later chapter: ‘These were Gauls, with perhaps some Germans, and were highly thought of…’ This was in the context of the composition of a Roman army before a campaign.

I am unsure why the author (who is clearly a highly knowledgeable scholar) felt the need to include these passages in the introduction – perhaps pressure from an increasingly ‘woke’ academia? Either way, I would sincerely wish the introduction could be altered for future editions. I must admit that I got quite annoyed by this, but decided to continue reading anyway – which I am glad I did.

The Corded Ware Culture

Although the author does not discuss this, I thought it would be reasonable to mention the great Corded Ware Culture. The Corded Ware Culture came about as a result of the invasion of Steppe Pastoralists (sometimes known as Indo-Europeans or Aryans) from today’s Ukraine into Central Europe. There, they met (or conquered, rather) the Early European Farmers – and from this union the Corded Ware Culture was born. To somewhat simplify matters, the Corded Ware Culture gave rise to the Germanic, Latin (i.e. Roman), Celtic, and Slavic peoples of Europe. Not only that, but the origins of the Iranian (Persian) and Vedic cultures can also be traced to the Corded Ware Culture. For more information, see the following video by Survive the Jive: Aryan Invasion of India: Myth or Reality?

Moreover, when observing the picture below, it becomes apparent why an entity such as myself, carved out of Swedish granite, would find an appreciation for and, to a certain extent, affinity with ancient Iran and India.

Dark green = genetical closeness. Thanks to Waters of Memory (active with that username on Telegram, X, and Instagram) for the picture.

The Persian Dynasties

There were three great Persian dynasties of antiquity. First and foremost, the Achaemenids – the rivals of the Greeks that would ultimately perish under the onslaught of Alexander the Great. The second dynasty, the Parthian one – the Arsacids – emerged when the Seleucid Empire disintegrated. From a Roman perspective, the Parthians are perhaps most famous for their victory over Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC. The Parthians were succeeded by the Sasanians in AD 224, who would rule up until the Arab conquests of the seventh century. The latter two dynasties are (alongside the Romans) the focus of the book.

Shapur – King of Aryans

One of the great kings of the Sasanian dynasty was Shapur I. The author shares the following epic passage that was found on a monument:

‘I am the Mazda-worshipping divine Shapur, King of Kings of Aryans and non Aryans, of the race of the gods, son of the Mazda-worshipping divine Ardashir, King of Kings of the Aryans, of the race of the gods, grandson of King Papak, I am the Lord of the Aryan nation.’

Adrian Goldsworthy – Rome and Persia. Page 247.

I found this particularly interesting – as well as poetically beautiful. Pictured below: Roman Emperor Valerian submits to Shapur I.

How Did the Romans Counter the Parthians?

The very word Parthian conjures up an image of a horse archer (at least it does for me, having grown up with Rome: Total War), so it was interesting to read about how the Romans countered these forces. The author highlights three aspects of the strategy of a general named Ventidius. The first was to only fight on ground of his own choosing. And, moreover:

‘Secondly, the Romans did not employ a static defence but counter-attacked with their legionaries and other troops and were able to move to hand-to-hand combat and win. Thirdly, Ventidius supported his legionaries with large numbers of light infantrymen armed with missile weapons. His slingers are singled out for their effectiveness, and it is claimed that they outranged the Parthians’ horse-archers.’

Adrian Goldsworthy – Rome and Persia. Page 116.

Seleucus I and Chandragupta

Although the conquests of Alexander (and the wars of his successors) belong to the era of the Graeco-Persian rivalry, the author introduces the geopolitical situation in the region after the conquest. He notes the following regarding the Seleucid Empire:

‘Territory in India was lost early on, in part through a deal between Seleucus I and Chandragupta, the charismatic creator of an empire in central and northern India. The Seleucids withdrew voluntarily from the lands around the Indus and in return were supplied with war elephants to employ in the funeral games.’

Adrian Goldsworthy – Rome and Persia. Page 49.

The funeral games is a reference to the Wars of the Diadochi (fought between Alexander’s successors). I have had a certain liking for and interest in the Seleucids ever since playing the aforementioned Rome: Total War when I was 14. On a related note, I read Valerio Massimo Manfredi’s trilogy about Alexander during this time as well (a trilogy I remember with fondness). Being one of Alexander’s generals, Seleucus has a prominent role in the trilogy.

Jesus – A God Among Many

As I have noted elsewhere, the polytheistic Romans (and indeed Europeans in general) were quite open to adding other Gods into their existing pantheon. On this note, I found the following passage interesting:

‘In a polytheistic culture, it is more than likely that many people revered the Christian God while continuing to follow older cults as well. One source claims that Severus Alexander added a statue of Jesus to the collection of deities especially important to him.’

Adrian Goldsworthy – Rome and Persia. Page 306.

Severus Alexander was emperor from 222 until 235.

My Own View of Jesus

Although this is not necessarily relevant to the book review per se, I thought to clarify my position on Jesus for good measure (as I have done on numerous occasions before). I always show respect for Jesus – as he has been an important individual for many of my ancestors. He is, moreover, still an important individual to some supporters and friends of mine – although the overwhelming majority are Pagans, as I am myself.

Mithra and Mithras

Enjoyers of my content will be familiar with Mithras. Just as some accepted Jesus into their pantheon, so were there many (primarily soldiers) who embraced Mithras. The author shares the following in regard to the cult:

‘In the Roman empire, the cult of Mithras built up a significant following, devotees attracted by its secret rituals, initiating them over time to higher grades within the order. Mithra was an Iranian god of great antiquity, within the Zoroastrian pantheon and much revered by many Parthians, especially among the nobility. The Roman cult drew inspiration from this tradition, since the distant and exotic has a natural appeal for many people, so the god was depicted in eastern dress and temples built to resemble caves to invoke old stories about the god. Yet the details were garbled, probably beyond recognition for traditional worshippers of Mithra, and everything tailored to suit the tastes of the Greco-Roman world. Plenty of the followers of Mithras were equestrians, including army officers, and there were never the slightest suggestion that their cult made them anything other than patriotic Romans. Similarly, reverence for the Greek tradition did not make subjects of the Arsacids automatically disloyal.’

Adrian Goldsworthy – Rome and Persia. Page 196.

Enthusiasts of the Mithras cult will perhaps be interested in The Mysteries of Mithras by Payam Nabarz that I reviewed a while back (review). To clarify – Mithras is the Roman God and Mithra is the Iranian God. I will discuss Mithras at length in a podcast episode (I have a few episodes planned before that, however).

Cicero’s Military Exploits

Cicero is best known as a statesman and a lawyer. Admirers of him will perhaps be happy to learn that he also acquired military success:

‘Cicero launched an offensive against the communities of Mount Amanus, who were fiercely independent and prone to raiding. This was partly to exercise his troops and partly to give a display of Roman strength to the mountain tribes and allies in the wider area. The orator and highly reluctant governor, let alone soldier, did well enough to hope for a triumph.’

Adrian Goldsworthy – Rome and Persia. Pages 102-103.

My admiration for the man did indeed increase upon reading about his participation in the war against the Parthians – especially since Cicero (as the author hints at in the quote above) was not a great enjoyer (by Roman standards, at any rate) of military matters, thus making his exploits even more laudable.

The Two Eyes of the World

One of the most interesting insights in the book (and there are plenty of them) is the one that illustrates how the Romans and Persians viewed each other (at times):

‘A sixth-century source claims that Narses I sent a trusted advisor to Galerius around 299. This man compared the Roman and Persian empires to two lamps; like eyes, ‘each one should be adorned by the brightness of the other’, rather than seeking to destroy. The imagery may be genuine, for near the end of the sixth century a king of kings sent a letter to the emperor stating that it was the divine plan that ‘the whole world should be illuminated… by two eyes, namely by the most powerful kingdom of the Romans and by the most prudent sceptre of the Persian state’, who between them held down the wild tribes and guided and regulated mankind.’

Adrian Goldsworthy – Rome and Persia. Page 330.

Quite a beautiful display of mutual respect!

Conclusion

At 494 pages, Rome and Persia explains the relationship between the Romans and Persians in a fully satisfactory manner. It contains plenty of valuable insights – in fact, the next episode of The Greatest Podcast will be dedicated to this topic and will have this book as its main reference.

I can definitely recommend the book – with the caveat that the introduction is not of the same quality as the rest of the book. In fact, I would even encourage the author to replace the introduction with a chapter about the shared origins of Rome and Persia – and perhaps a discussion about the commonalities between their religions.

Pax by Tom Holland

Posted on September 13, 2023

I have read Pax – War and Peace in Rome’s Golden Age by Tom Holland. I have always had a keen interest in Roman history – as I am sure all men of culture have. I could label either Roman or Mediaeval history as my first love in this regard. Thus, I said it would be my pleasure when the publisher asked if I wanted to review the book.

As the title of the book suggests, it details the Roman world of Rome’s golden age (i.e. when Roman power was at its zenith) – from the tumultuous Year of the Four Emperors (AD 69) to the reign of Hadrian (AD 117 to 138). The book is very well written and presents the principal events and wars of the era in a clear and gripping way.

The book contains the following chapters:

I. The Sad and Infernal Gods

II. Four Emperors

III. A World at War

IV. Sleeping Giants

V. The Universal Spider

VI. The Best of Emperors

VII. I Build This Garden for Us

Transgender Queen!?

In Chapter I, the author gives much attention to two individuals – Queen Poppaea and a eunuch also named Poppaea. The author mentions that:

‘And it was to Greece, as it so happened, that the boy transformed into Poppaea, only a few months after the operation that had made him a woman, had been taken by Nero. Borne in a litter appropriate to an empress, the new Poppaea had toured a succession of the festivals for which Greek cities were famed.’

Tom Holland – Pax. Page 52.

Later in the chapter, the author refers to the eunuch as a maimed parody:

‘Otho, by seizing the maimed parody of his former wife, had known full well what he was doing. Poppaea served as a totem. To own her was to signal a readiness to play the role not merely of a Caesar, but of a Nero.’

Tom Holland – Pax. Page 72.

A generous interpretation of why the author would say that ‘the operation that had made him a woman‘ is that it could be a poetic way to say that they attempted to make a eunuch as feminine as possible. Another way to explain it is that the author lives and works in the United Kingdom – and thus has to contend with a notoriously repressive regime. Just as one would expect an author in the Eastern Bloc during the Soviet times to formulate himself in a certain way, so can one suppose that the author does something similar here.

Perhaps I am reading too much into it, and whatever the reason the author had for formulating himself thus, it should not discourage anyone from reading an otherwise excellent book.

BBC Rewriting History

In the preface of the book, the author notes the following:

‘BBC, in a recent film made for children about Hadrian’s arrival in Britain, amended chronology so as to portray the governor of the province at the time as African.’

Tom Holland – Pax. Page 4.

A less polite, but perhaps more accurate, way to state it would simply be to say that the BBC, a propaganda organ, falsifies history. Either way, my respect to the author for calling our their falsehoods.

A Passion for Honour

The author gives plenty of attention to the legions – which is good, considering their central role in Roman history. He elaborates on the rivalry between the various legions and the passion for honour that the Roman military traditions inspired. As I noted in Dauntless (2021) – competition breeds excellence. I also use the example of the Roman legions in my upcoming Demigod Mentality (September 2023) to exemplify how rivalries can serve as a catalyst for greatness. To understand the prowess of the legions one needs to understand the importance of the esprit de corps.

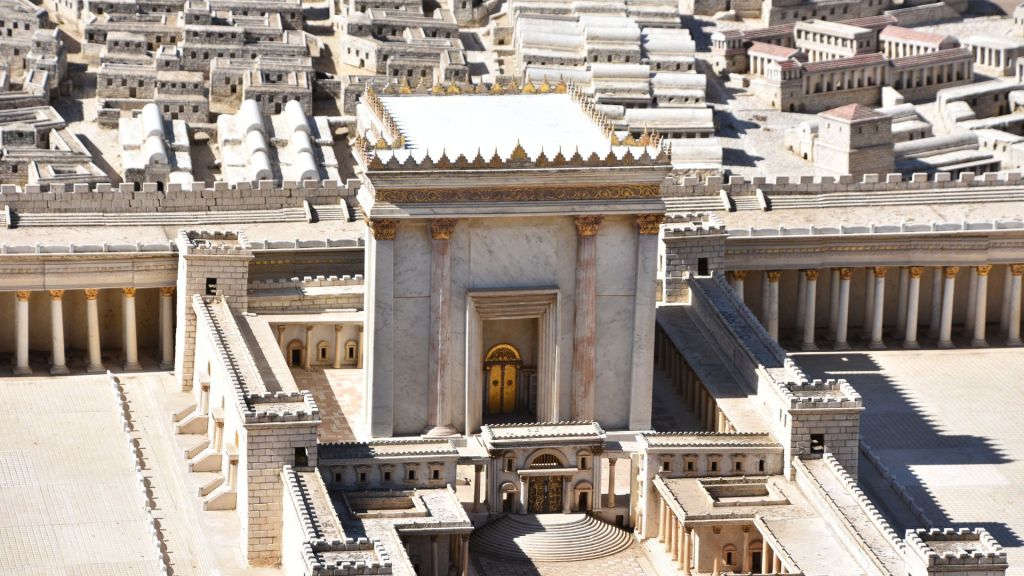

Rome vs Judaea

One of the most significant conflicts during the Golden Age of Rome was the one in Judaea. The conflict was not a single war, but rather a continuous conflict involving different factions – the two main ones being the Romans and the non-Hellenised Judaeans (i.e. the Judaeans who did not want to assimilate into the Graeco-Roman world). This conflict was not restricted to Judaea – for example, the Judaean population in Cyrene rose up in a full-blown uprising, and Alexandria saw running battles in the streets between Greeks and Judaeans.

The author shares the following valuable insight:

‘Much that makes what today we call ‘Judaism’ distinctive – the role played by rabbis, synagogues, the Talmud – constitutes less a preservation of what had existed before the wars against the Romans than an adaptation to its loss.’

Tom Holland – Pax. Page 12.

Understanding the conflict between Rome and Judaea is of paramount importance for understanding Nietzsche’s teaching on master and slave morality – and much of world history for that matter.

Beautiful Quote on Trajan

Astute enjoyers of my book reviews know that I always appreciate inspiring quotes. Here is a description of Trajan, often described as the best of emperors:

‘Imperator Caesar Nerva Trajanus Augustus. Tall, broad-shouldered and weather-beaten after the many months he had spent under canvas, he exuded a quality of virtus, of manliness, such as a Roman from the most primitive days of the city.’

Tom Holland – Pax. Page 309.

Conclusion

The book is 399 pages and strikes a good balance between being concise and containing a satisfactory amount of detail. The author has released books about the previous eras of Roman history as well – perhaps I shall read them later! I enjoyed the book and can recommend it to the enjoyer of history.

Tales & Legends of the Devil by Claude & Corinne Lecouteux

Posted on September 5, 2023

Our study of folklore continues! Thus, I have read Tales & Legends of the Devil – The Many Guises of the Primal Shapeshifter by Claude & Corinne Lecouteux. The book contains stories involving the Devil, from all over Europe. The book is structured into seven chapters, which are the following:

Chapter I: The Devil as a Suitor

Chapter II: The Devil and His Family

Chapter III: The Swindled and Battered Devil

Chapter IV: In the Devil’s Service

Chapter V: A Visit to Hell

Chapter VI: The Devil and the Church

Chapter VII: Singular Tales

The stories are, as suggested by the titles of the chapters, sorted in themes.

The most interesting insights gained from reading all of the stories is that the Devil is not quite the fearsome Prince of Evil that one would except. Rather, he is usually presented as an archetypal Trickster God. Upon reading many of the stories, I was reminded of Gaunter O’Dimm, whom men of culture will have encountered when playing the masterpiece The Witcher 3: Hearts of Stone. So, a powerful individual that tempts individuals into diabolic pacts – but still an entity that can be defeated by the wit or goodness of humans.

Many of the stories – especially those presented in Chapter III: The Swindled and Battered Devil – conclude with the human getting the better of the Devil.

A common theme in many of the stories is, as one may expect, that one who enters a pact with the Devil will benefit in the short terms but at a great cost later on.

At 209 pages, the book is a concise read and gives a good overview of the Devil in European folklore.

Phantom Armies of the Night by Claude Lecouteux

Posted on August 26, 2023

I have read Phantom Armies of the Night: The Wild Hunt and the Ghostly Processions of the Undead by Claude Lecouteux. As the title suggests, the book explores the legend of the Wild Hunt and similar folklore stories about the restless dead. The author introduces various tropes found in primarily French and German mediaeval myth and discusses them throughout the book. Just as with the Traditional Magic Spells for Protection and Healing (review), the book should be read as a study of European folklore.

The Golden One’s Wild Hunt

Those who have been with me for some time know that I sometimes make videos titled The Wild Hunt Challenge, where I present a number of challenges to complete (often related to training and reading). By using the name of the Wild Hunt, I seek to evoke a sense of enthusiasm, a sense of divine energy, and a hunger for life. Envision yourself as being swept up by the energies of Odin and the Wild Hunt as you embark upon an endeavour! I elaborate more on this in my upcoming book Demigod Mentality (September, 2023).

The Mediaeval Church and Folklore

As we have noted in several other book reviews and in a few Podcast episodes, the Christianity of the Middle Ages was rather a syncretic Paganism and Christianity. One could even say that the Christian mythos of the Middle Ages was a continuation of the existing one (with the addition of new characters and places):

‘The medieval church invented nothing. It picked up preexisting elements so that it could remodel them. It therefore created its own mythology from an older substratum, and this mythology soon fell into the public domain, where it continued to nourish beliefs and legends.’

Claude Lecouteux – Phantom Armies of the Night. Page 3.

Most of the stories presented in the book date from the (nominally) Christian period. The reason for this is that there are more sources to draw upon from that period than from earlier periods. On a personal note, I would have preferred a deeper investigation of the earliest roots of the legend, but I understand that such a discussion lies outside the scope of this book. Moreover, Claude Lecouteux is a scholar and presents evidence as he finds it, so I respect his choice to not speculate too much.

Pictured below: The Wild Hunt of Odin (1872) by the Norwegian artist Peter Nicolai Arbo.

The Wild Hunt in Indo-European Myth

The author concludes that it is hard to find a direct common source for the Wild Hunt. He does, however, note that some researchers have compared the Wild Hunt to the Vedic God Indra’s companions – which indicates an Indo-European origin of the myth. The author shares the following quote by Jan Gonda, who describes Indra’s companions thus:

‘Large and powerfully strong and dreadful in appearance, they cleave the air over mountain and hill, armed with their glittering spears. Admirable and irresistible, they travel in their sparkling golden chariots pulled by red-roan horses or gazelles. All tremble before them, even the earth and the mountains.’

Jan Gonda – Les Religions de l’Inde I: Védisme et Hindouisme anciens

This does indeed sound quite Indo-European. Important to note here is that the Indo-European influence in Iran and India came from the Corded Ware culture of central Europe. The modern population that is the closest genetically to the Corded Ware culture is the Swedish one. Thus, one should not be confused by the term Indo-European – which is why some prefer the term Aryan. Vedic spirituality was a result of the Aryan Invasion (for more information, watch this video: Aryan Invasion of India: Myth or Reality?).

Odin and Shamanic Doubles

In an interesting passage in the chapter titled Odin and the Wild Hunt, the author notes the following:

‘In 1980 a disciple of Höfler, Christine N. F. Eike, published an extensive study on the Oskoreia, the name for the Mesnie Hellequin in Norwegian folk traditions that picked up on the trance theory, noting that the manifestations of the winter-nights troop seem to reflect phenomena, such as forming Doubles, well known in shamanic traditions. This finally explains why it is logical for Odin to have been made the leader of the troop: he was considered the “god of ecstasy” (ekstasegud).’

Claude Lecouteux – Phantom Armies of the Night. Page 205.

The Oskoreia and the Mesnie Hellequin refer to the Wild Hunt. In the same chapter, the author refers to the great Jacob Grimm:

‘In quest of a German mythology, Jacob Grimm studied the theme of the cursed huntsman, which he compares to the Mesnie Hellequin, known as the Furious Army and the Wild Army in the regions east of the Rhine River. Starting in 1835 he sees in its leader a form of Odin that had been downgraded by Christianity to the rank of a ghostly figure.’

Claude Lecouteux – Phantom Armies of the Night. Page 203.

I present these quotes without further comment at the moment, but we will return to this topic in coming reviews, videos, and Podcast episodes.

Epic German Verse

The following verse appears on the first page of the chapter titled The Troops of the Dead. I found it particularly epic:

‘Es stehn die Stern am Himmel,

Es scheint der Mond so hell,

Die Toten reiten schnell…’

This is translated in the book as follows:

The stars sparkle in the firmament

The moon shines clear

the dead ride fast…

Hell (bright in German) rhymes with schnell (fast). The verse comes from the folk song Lenore. The poem was written by German author Gottfried August Bürger in 1773. Aside from the beauty of the verse, it is interesting to observe that this procession takes place when the moon shines bright (full moon) since we have discussed the influence of the full moon on previous occasions.

Pictured below: Sturm und Drang moment in Marburg, Germany.

Theodoric the Great and the Huntsman

In the Eckenlied (an anonymous 13th-century Middle High German poem), Theodoric the Great (Dietrich von Bern in German mediaeval literature) encounters a giant figure named Fasolt. Fasolt is clad in armour and has his hair braided and carries a hunting horn; he is accompanied by a pack of hounds. In the story, he pursues a wild maiden named Babehilt, who seeks the protection of Dietrich. Fasolt enters a rage and demands to know why Dietrich would deny him his prey. Since Dietrich is wounded, Fasolt does not engage him in combat. My initial thought upon reading this was to think of Orion of Warhammer – who is a figure based on these themes as well as on the Celtic God Cernunnos (pictured below). Cernunnos is associated with beasts, fertility, hunting, and nature. Although the author of the book does not make this statement, I am personally of the opinion that Cernunnos surely must have inspired later tales of the Wild Hunt.

The Cursed Hunter and Michael Beheim

One common trope associated with the Wild Hunt and the restless dead is the cursed hunter. The author shares one such example from a Meistersang (master + song) by Michael Beheim. In that story, Count Ebenhart of Wirtenberg encounters an apparition during a hunt. The apparition tells the count that he was so passionate about hunting that he asked God if he would permit him to hunt until Judgement Day. The apparition then says that to his great misfortune the wish was granted, and that he had now hunted for five hundred years.

The author notes that the apparition was punished for hunting on a Sunday, for damaging crops, and for slaying a stag in a church.

On a related note, the name Michael Beheim may be familar for appreciators of Vlad Dracula. Beheim was Dracula’s contemporary and composed a poem about him. I first encountered the name of Michael Beheim in Dracula, Prince Of Many Faces by Florescu Radu R. and Raymond T. McNally (the book I relied on for my Podcast Episode 20. Vlad Dracula).

Hellequin

The English word Harlequin stems from the French word Hellequin. The author says the following about the word:

‘In France, the name Mesnie Hellequin gradually came to mean people who assembled to commit acts contrary to good character and morality…’

Claude Lecouteux – Phantom Armies of the Night. Page 206.

The Mesnie Hellequin is, as already mentioned, a word used in mediaeval French literature and myth to describe Wild Hunt-like ghostly processions.

Conclusion

Phantom Armies of the Night is a good book and serves as a good starting point for anyone who wishes to learn more about mediaeval folklore. On a personal note, I would have liked a more thorough discussion about the Odinic and ecstatic aspect of the legend. However, as already mentioned, the book should be read as a study of folklore as opposed to a study of pre-Christian religion.

Onwards and upwards!

You must be logged in to post a comment.